Creating opportunities for visitors to reflect on connections between the Holocaust and their present lives

The mandate of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) calls on us “to enhance the public’s understanding of human rights, to promote respect for others, and to encourage reflection and dialogue.”[1] In practice this means that in addition to presenting historical information on human rights, we are tasked with facilitating opportunities for visitors—including students in school programs and members of the general public—to engage with the past in a manner that can reveal personal insights directly relevant to their day-to-day choices, actions and lives in the present.

Given this call for reflective engagement, a crucial consideration for the CMHR’s Examining the Holocaust gallery (for which I serve as curator) has been the importance of shrinking the conceptual distance between the Holocaust and our visitors. Of course, many visitors have some familiarity with the Holocaust, the Nazis’ genocidal attempt to eradicate the Jewish people before and during the Second World War. It is one of the most well-documented, extensively researched, and widely taught and represented atrocities in human history. Aspects of it have become iconic of humanity’s potential for depravity: the decrepit and crowded conditions of the ghettos; deportations; selection processes at concentration camps that determined if one would be immediately killed or first subject to forced labour; gas chambers; the mobile killing squads.

But is it possible that broad familiarity with such aspects of the Holocaust can potentially obscure other crucial components of its brutally efficient system of genocide? Can the sheer scale of the Holocaust and the unfathomability of some of its most violent features challenge a representational strategy that calls for reflective personal engagement with the historical past? How can individuals locate themselves within a history where the most recognizable reference points are so far removed from their present-day experiences and perspectives?

As we developed the Examining the Holocaust gallery, such questions loomed large in my mind, inspired by a memorable sequence in Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, in which Nazi officer Amon Goeth (played by Ralph Fiennes) casually shoots inmates from the balcony of his villa at the Płaszów concentration camp. These moments undoubtedly convey a sense of the brutality that was ubiquitous during the Holocaust. However, viewing this sequence as a spectator, it is very easy to disassociate myself from the casual horror of Goeth’s actions. While I greatly admire Schindler’s List,[2] for me, this particular sequence does not provoke introspective consideration on my engagement with the past, or on my own moral agency in the present, as Goeth’s murderous violence strains the limits of my experiential imagination and sense of self.

It is such subjective distancing that the CMHR mandate cautions against. In developing Examining the Holocaust specifically, the mandate reminded us to be wary of too readily giving visitors a moral “out” from reflecting on their own biases, perspectives and actions while engaging with information about the Holocaust. We wanted to be careful to not simply position the Holocaust as a negative and distant object lesson that embodies what we do not want for ourselves, our children, and our society. Rather, our aim is to encourage visitors to find points of connection and relevance between the Holocaust and their present lives.

One of the exhibits in Examining the Holocaust that seeks to inspire such personal reflection is titled “Complicit in Genocide” (Fig. 1).[3] It is a two-story display case that calls attention to some of the “smaller,” less iconic actions that contributed to the Holocaust, and invites visitors to think about the impact that their own actions can have for human rights today.

Fig. 1: “Complicit in Genocide” exhibit in the Examining the Holocaust gallery (CMHR)

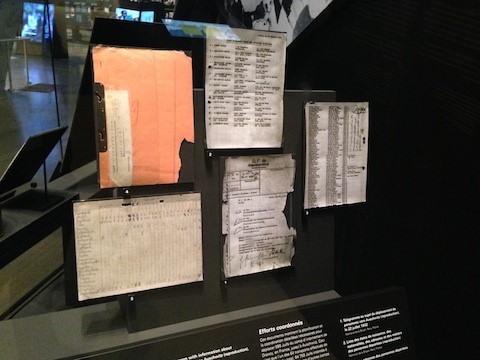

The exhibit design uses juxtaposition to convey the relationship between individual actions and the Holocaust as a whole. The backdrop consists of two large aerial shots of Auschwitz. The size of this backdrop and imagery of the Holocaust’s most infamous concentration camp is intended to symbolize the massive scale of the Holocaust and the brutal efficiency that allowed thousands to be murdered daily. Displayed in front of these images is a small sampling of objects that represent some of the individual actions, seemingly minor on their own, that nonetheless played a part in allowing the Holocaust to be perpetrated on the scale that it was. Visitors are encouraged to consider how the architectural plans for Auschwitz had to be drafted by someone; how an individual had to type up transport lists that made it possible to deport huge groups of people to their deaths (Fig. 2); how someone had to actually order canisters of Zyklon B for the gas chambers.

The exhibit is rounded out by a chilling photograph of Nazi soldiers and support staff from Auschwitz on break at a resort near the camp (Fig. 3). Unlike many representations of Nazis that visitors may be familiar with, this image is striking for how happy and carefree—indeed, how human—they look. Aside from their uniforms, this could be a picture of friendship anywhere. Yet these individuals are among those whose choices and actions contributed to the Holocaust.

The interpretive key to this exhibit is that the Holocaust was made possible by thousands of individual decisions and actions—some large, but many smaller. While it can be easy to lose sight of the latter when thinking about the Holocaust in its totality, opportunities for self-reflection are lost if they are overlooked. It is not difficult to distance oneself from a concentration camp commandant shooting innocent victims from his balcony. But contemplating an administrator preparing a transport list to facilitate deportation to a death camp may encourage a greater sense of pause, and perhaps even discomfort as visitors reflect on how their own, sometimes seemingly minor choices can have profound human rights significance.

While “Complicit in Genocide”

focuses on the Holocaust specifically, the idea that individual choices can

contribute positively or negatively

to human rights is universal. Our hope is that the exhibit’s juxtaposition

of the Holocaust’s enormity with some of the smaller actions that enabled it can

offer visitors a means to read themselves into the past, and vice versa; to consider

the motivations that inform the choices they make in their own lives, and on

how their actions might—on their own or combined with those of others—contribute to the promotion of human rights for all.

[1] https://humanrights.ca/about/mandate-and-museum-experience

[2] For a more fulsome analysis of Schindler’s List by the author, see Jeremy Maron, “Affective Historiography: Schindler’s List, Melodrama and Historical Representation,” Shofar 27.4 (Summer 2009), 66-94.

[3] For a discussion on the development of the CMHR’s Examining the Holocaust gallery as a whole, see Jeremy Maron and Clint Curle, “Balancing the particular and the universal: examining the Holocaust in the Canadian Museum for Human Rights,” Holocaust Studies 24.4 (2018), 418-444.

Jeremy Maron, PhD, is a Curator at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.